Who Collected Stamps?

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 Quantifying collectors and analyzing their demographics is difficult, because most individuals collected outside of formalized clubs. Beginning in the late-nineteenth century, consistent media coverage of famous collectors, stamp production, and collecting practices exposed non-collectors to the hobby and taught them that many people saw something special in stamps and spent time collecting them.

¶ 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0

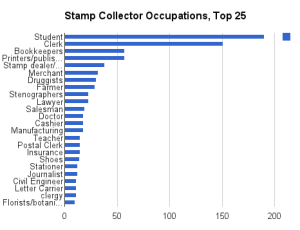

Occupations of stamp collectors, Rogers Philatelic Blue Book, 1893

Occupations of stamp collectors, Rogers Philatelic Blue Book, 1893

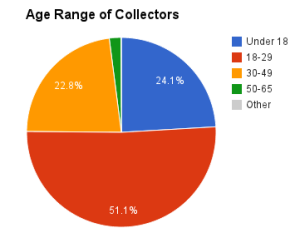

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 Kings, queens, lords, czars, and American politicians put a public face on philately in late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century periodicals, but most American collectors were not famous or worthy of headlines. They worked in a variety of occupations and lived both in rural and urban areas. Rogers’ American Philatelic Blue Book of 1893 indicated that late-nineteenth-century stamp collecting was truly a pursuit of young adults who worked in a variety of occupations. The Blue Book listed more farmers than doctors and more clerks than bankers, and showed that skilled workers such as electricians, carpenters, blacksmiths, quarrymen, patternmakers, and coal miners publicly identified themselves as stamp collectors.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 More than half of the 2000 respondents did not belong to a philatelic association, but they must have occasionally read a philatelic paper to know about Rogers’s free listings in this directory.

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 Directories, like Rogers’s Blue Book and others printed by prominent philatelic publisher, Mekeel’s, showed that collectors lived in big cities and small towns across the U.S. Most collectors listed themselves by their last name and first initials, making gender speculation difficult, but the occupations listed indicate that most probably were male. Rogers compiled his directory to grow membership in the American Philatelic Association, of which he was a member. Rogers’ Blue Book provided some excellent information about collectors not found in other directories of collectors (such as Mekeel’s), particularly age, occupation, and affiliations. Out of the 2000 collectors listed, only 1718 were American collectors, and only 54 identified themselves solely as dealers. Not surprisingm Roger’s did not ask about the race or gender for the listings. ((Albert R Rogers, Roger’s American Philatelic Blue Book, Containing a List of Over Two Thousand Stamp Collectors and Dealers, Philatelic Papers and Societies, with Valuable Information Concerning Them, and Seven Hundred Advertisements of Collectors and Dealers (New York: Albert R. Rogers, 1893). He placed ads in various stamp publications and sent notices to stamp clubs in the U.S. and Canada to gather the names in this directory. See my transcription of some of these totals. A handful of individuals listed a business or school address so it is possible to see the occupations of these collectors. It is unclear whether some of those listed under colleges are students, staff, or professors. Mekeel required payment of $1.00 to be listed in his directory, but all of those listed also received free space for an exchange notice where they described what type of stamp varieties they collected. Mekeel, Mekeel’s Stamp Collectors’ and Dealers’ Address Book, 138. ))

¶ 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0

Breakdown of Stamp Collectors’ Ages, Rogers Philatelic Blue Book of 1893

Breakdown of Stamp Collectors’ Ages, Rogers Philatelic Blue Book of 1893

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 Circulating addresses also gave collectors the opportunity to build communities and foster connections across geographies via the mail system by writing to others seeking to trade or buy stamps. By the 1890s, stamp collecting was an established pastime shared by many men working in white and blue collar occupations across the country who had a few extra dollars and hours to spend on a hobby, and some of them joined newly-forming philatelic clubs.

Women Collectors

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 For a hobby that men appeared to dominate, at least publicly, it is intriguing that women played a formative role in shaping the mythology of early philately. One philatelic writer claimed that the first gatherings of stamp collectors in Paris in the 1860s were hosted and attended by women who exchanged their duplicate stamps on Sunday afternoons in the Tuilleries Gardens. When the postage system was still new in Britain, women collected stamps featuring the profile of reigning monarch Queen Victoria. In the 1880s, women’s magazines such as Godey’s Lady’s Book and Ladies’ Home Journal proposed that stamp collecting was an appropriate activity for women. Because it was an indoor amusement, “restful” and “quieting after the mind has been busily occupied with duties,” it was viewed as a proper way for middle-class women to spend their leisure time. Women were well suited to the pastime because it involved creativity—when arranging a collection—that capitalized on their “natural artistic tastes.” Godey’s instructed women how to decorate tables with stamps, and Ladies’ Home Journal taught women how to throw a “fad party” that included a stamp collecting hunt. ((“Work Department,” Godey’s Lady’s Book 101, no. 605 (1880): 477. Reported by London Tit-Bits but reprinted in “Costume of Postage Stamp,” Eagle County Blade, 1905. MacClung Strickler, “To Make a Postage Stamp Collection,” Ladies’ Home Journal 18, no. 4 (1901): 6. In the fad party, stamps were hidden around the house and participants had to find as many stamps as possible until a bell sounded to end the hunt. Bertha A. Law, “A Novel Fad Party,” Ladies’ Home Journal 21, no. 12 (1904): 57.)) This style of collecting and using stamps by women was seen by some club philatelists, as noted by one in 1919, as lacking “the great principles of philately.” ((“The Beginning of Philately,” American Philatelist 33, no. 5 (1919): 161. Other stories referenced included how one woman placed an advertisement in the London Times in 1841 seeking canceled stamps to decorate her dressing room. And in 1842, Punch poked fun at female collectors who anxiously sought out the Queen’s head by collecting images of Victoria postage stamps.)) Those principles emerged with the establishment of a network of philatelic clubs in the 1870s, ‘80s, and ‘90s that guided members to organize and analyze stamps in particular ways.

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 Club philatelists, for example, never advocated decorating with stamps, but rather urged collectors to protect and save stamps carefully in albums. Since collecting and presenting stamps in those ways were not valued by philatelists, most material evidence of those pieces was not saved. Nonetheless, articles in women’s magazines exposed women to the hobby even when they were not accepted into many philatelic clubs in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Non-Club Collectors Influenced by Popular Media

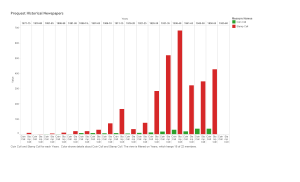

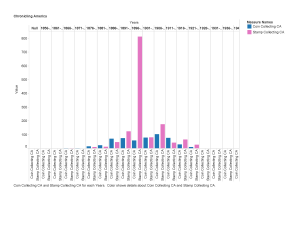

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 The popular press also exposed the diverse American public to information about stamp collecting and increased interest that led to broader adoption of the hobby. Whether extolling the values of collecting, perpetuating the idea that anyone could find a rare stamp in a box of old letters, or by framing stamp collecting as a “mania,” stamp collecting was in the news. The presence of stamp collecting articles in U.S. newspapers and magazines was not overwhelming, but the numbers of articles increased greatly from the 1870s to the 1930s, marking a sharp growth in exposure never shared by similar hobbies, including coin collecting.

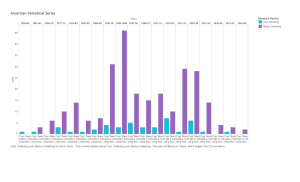

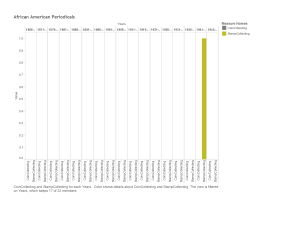

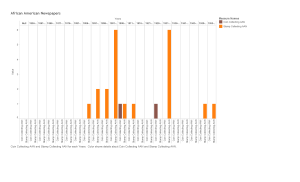

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 By searching the contents of the Proquest Historical Newspapers database, the Proquest American Periodical Series, and the Readex databases of African American Newspapers and African American Periodicals, it is possible to see an overall increase in numbers of articles referring to philately and stamp collecting in the 1890s, and then again in the 1920s and 1930s.

¶ 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0

Search results from ProQuest Historical Newspaper database

Search results from ProQuest Historical Newspaper database

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 Articles first appearing in larger market papers, such as the New York Times and Washington Post were often reprinted in smaller markets papers, as found in the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America newspaper project representing regional and local newspapers, and in the African American newspapers.

¶ 14

Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0

Search results from the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America.

Search results from the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America.

¶ 15

Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0

Results from the American Periodicals Series Online

Results from the American Periodicals Series Online

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 The fewest total articles appeared in the African American press, meaning there was less casual exposure to philately than to readers of the major dailies.

¶ 17

Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0

Results from African American Periodicals, 1825-1995 collection, Readex

Results from African American Periodicals, 1825-1995 collection, Readex

¶ 18

Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0

Results from African American Newspapers, 1827-1998, Readex

Results from African American Newspapers, 1827-1998, Readex

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 As early as the 1870s, youth magazines promoted stamp collecting as an appropriate and educational activity for young people. St. Nicholas was among the first non-philatelic publications to devote valuable copy space to promoting stamp collecting. It published numerous articles on stamp collecting that offered primers to teach child readers about stamps from different nations and the practices of collecting. St. Nicholas began a trend that many other periodicals would soon follow. In 1910, the Christian Science Monitor began publishing regular articles on stamps for young readers and The Youth’s Companion started their stamp collecting column in 1919. ((Crawford Capen, “Stamp-Collecting: How and What We Learn From It,” St. Nicholas, An Illustrated Magazine for Young Folks, January 1894; “Stamps to Stick,” Youth’s Companion, March 20, 1919; Russell J. Reed, “Junior Philatelist,” Christian Science Monitor, August 13, 1910; ))

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 This trend spread to the dailies as well. In the late 1920s, the Los Angeles Times printed a regular hobby column that often included articles on stamps; the Chicago Daily Tribune began a Sunday stamp column in 1932; and the Washington Post added the “Stamp Album” to their Junior Post section for young readers in 1934. The New York Sun even bought ads in the Chicago Tribune inviting its readers to subscribe to the Sun’s Saturday paper specifically to read their special stamp collecting section. In 1936, the Philatelic Almanac listed 150 papers supporting stamp departments that generated regular articles or columns. ((“The Growing Interest in Phliatley,” Collectors Club Philatelist 11, no. 2 (April 19, 1932): 133; H.M. Harvey, “Philatelic Departments,” Mekeel’s Weekly Stamp News 46, no. 46 (November 14, 1932): 564; “Announcing a New Department on Stamps and Stamp Collecting,” display ad, Chicago Daily Tribune, September 4, 1932; J.C. Salak, “Philately,” Los Angeles Times, December 16, 1928, sec. L; “The Stamp Album,” Washington Post, July 23, 1933; “For Stamp Collectors,” display ad, Chicago Daily Tribune, May 2, 1934; and Frank L. Wilson, The Philatelic Almanac: The Stamp Collector’s Handbook (New York: H.L. Lindquist, 1936), 107-09. ))

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 With the emergence of commercial broadcasting in the U.S. in the 1920s, listeners not only tuned in to hear musicians and comedy acts, but also listened to stamp collecting programs. Newspapers listed daily programming from their home city and from other regions that reveal shows running from fifteen minutes to one half hour. Mekeel’s tracked philatelic radio programming and listed nine regular shows in 1932 broadcast from stations in Illinois, Georgia, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey. By 1936, more than 60 stations broadcasted philatelic shows. Those who listened regularly were exposed to stamp collecting practices and “the drama of the postage stamp.” ((I have not been able to locate any transcripts or recordings of these stamp programs. Powers’s programs were broadcast in different stations and markets. It is possible that the programs began because radio stations needed to fill air time and daytime programming lacked competition in the early days of broadcasting. “Today’s Radio Program,” <em>New York Times</em>, January 15, 1924, 21; “Today’s Radio Program,” <em>New York Times</em>, February 5, 1924, 17; “Today’s Radio Programs,” <em>Chicago Daily Tribune</em>, January 3, 1924, 6; “Radio Programs,” <em>Washington Post</em>, March 25, 1924, 16; “Broadcasts Booked for Latter Half of the Week,” <em>New York Times</em>, August 12, 1928, sec. XX, 16.; “Chicago Radio Talks,” <em>Mekeel’s Weekly Stamp News</em> 46, no. 39 (September 26, 1932): 476; “Radio Philately,” <em>Mekeel’s Weekly Stamp News</em> 46, no. 41 (October 10, 1932): 504.; and Frank L Wilson, <em>The Philatelic Almanac: The Stamp Collector’s Handbook </em>(New York: H.L. Lindquist, 1936), 110–11. For a few sources on the history of commercial radio, see Alice Goldfarb Marquis, “Written on the Wind: The Impact of Radio During the 1930s,” <em>Journal of Contemporary History</em> 19, no. 3 (July 1984): 385–415; Susan Smulyan, S<em>elling Radio: The Commercialization of American Broadcasting, 1920-1934</em> (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994); Susan J. Douglas, <em>Inventing American Broadcasting, 1899-1922</em>, Johns Hopkins Studies in the History of Technology (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987).))

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 As philatelic information spread in different media, stamp collecting attracted new practitioners and appealed to the interests of different people. Magazines, newspapers, and radio programs brought some activities that had been exclusive to philatelic clubs and publications out into a public realm. For collectors who did not belong to a club, especially for those excluded from clubs, this exposure increased their philatelic knowledge and allowed them to connect with the philatelic community through the media.

Comments

0 Comments on the whole Page

Leave a comment on the whole Page

0 Comments on paragraph 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1

0 Comments on paragraph 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2

0 Comments on paragraph 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3

0 Comments on paragraph 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4

0 Comments on paragraph 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5

0 Comments on paragraph 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6

0 Comments on paragraph 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7

0 Comments on paragraph 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8

0 Comments on paragraph 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9

0 Comments on paragraph 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10

0 Comments on paragraph 11

Leave a comment on paragraph 11

0 Comments on paragraph 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12

0 Comments on paragraph 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13

0 Comments on paragraph 14

Leave a comment on paragraph 14

0 Comments on paragraph 15

Leave a comment on paragraph 15

0 Comments on paragraph 16

Leave a comment on paragraph 16

0 Comments on paragraph 17

Leave a comment on paragraph 17

0 Comments on paragraph 18

Leave a comment on paragraph 18

0 Comments on paragraph 19

Leave a comment on paragraph 19

0 Comments on paragraph 20

Leave a comment on paragraph 20

0 Comments on paragraph 21

Leave a comment on paragraph 21

0 Comments on paragraph 22

Leave a comment on paragraph 22